The question we are often asked is where we get the cells for our art works. An interesting question that does not have a simple answer. This blog entry attempts to give an overview of our various practices within past projects focusing on the source of the biological material.

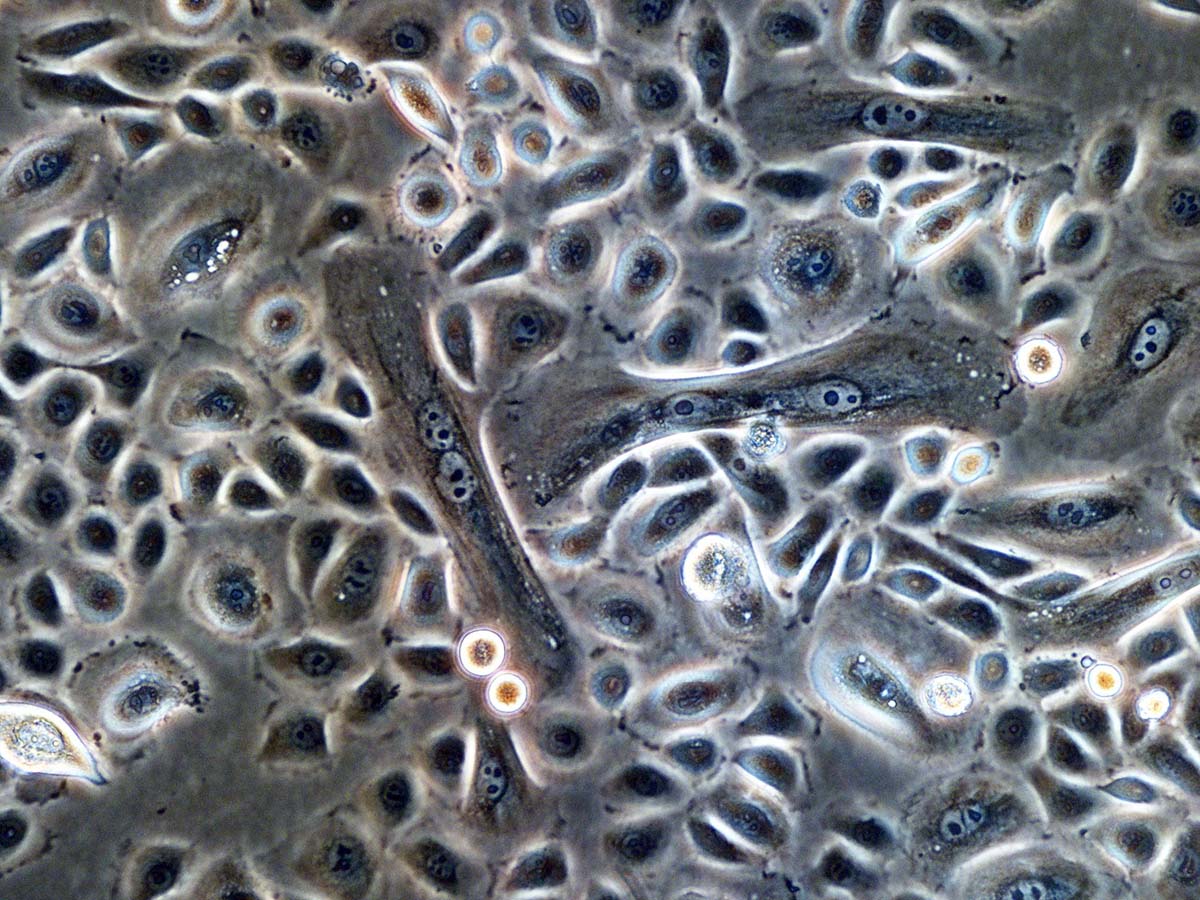

Most of the projects we developed in the early 2000s used cell lines that we purchased though on-line catalogues. Many companies sell cells lines for research such as the ATCC (https://www.atcc.org/en/Products/Cells_and_Microorganisms/Cell_Lines.aspx) or cellular dynamics (https://www.fujifilmcdi.com/) and more. Its quite common, in scientific research, to source cells from these companies. However, usually, it is quite expensive to buy the cells therefore, we often tried to find friendly scientists at the School of Anatomy, Physiology and Human Biology @ the University of Western Australia (SymbioticA is located within this school) that would share some of their cell stocks with us… and they often do. It’s quite a common practice for scientists to share cells between themselves.

Another avenue for sourcing cells was what we refer to as ‘scavenging’, mainly from primary tissue, cells that you cannot really source from commercial companies or those that cant be frozen and therefore need to be sourced fresh and alive. We would go into labs, look in the bins, and take the left over tissue that the scientists did not use for their own experiments.

We would like to emphasize that no matter how we source the cells there is a hard requirement in SymbioticA and UWA that application is sent to the ethics committees of the University to obtain permission to use of the cells.

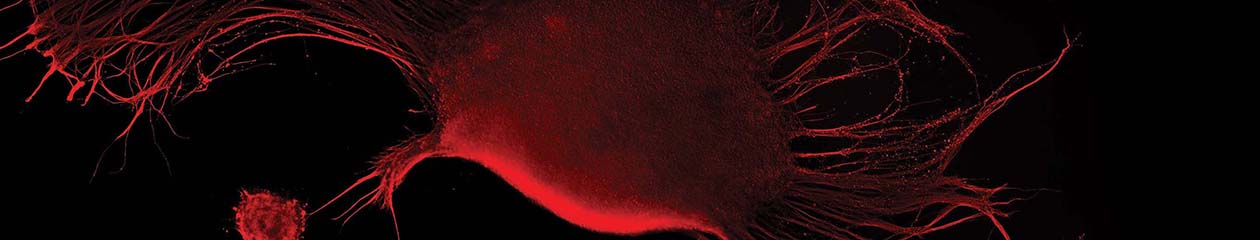

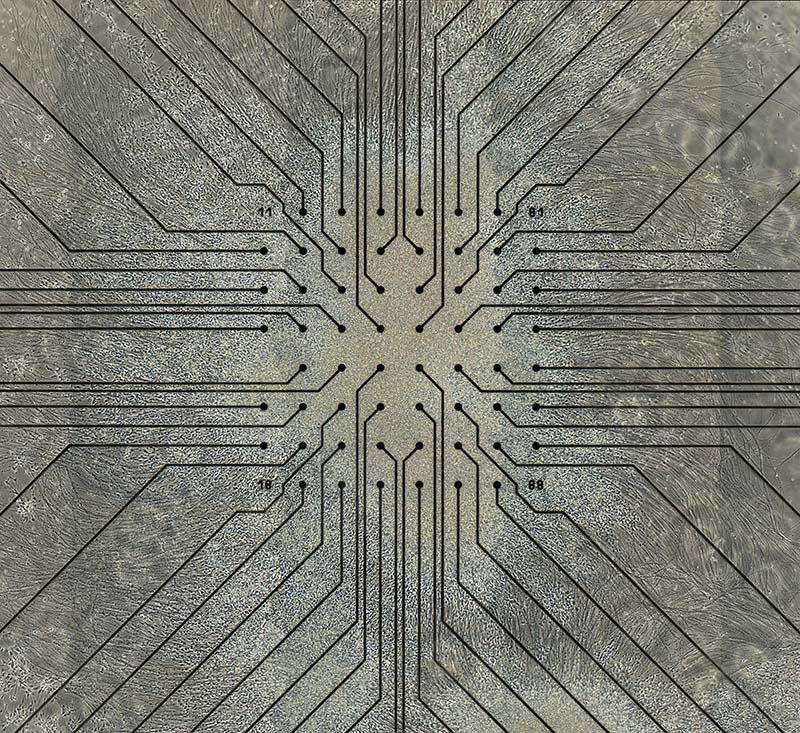

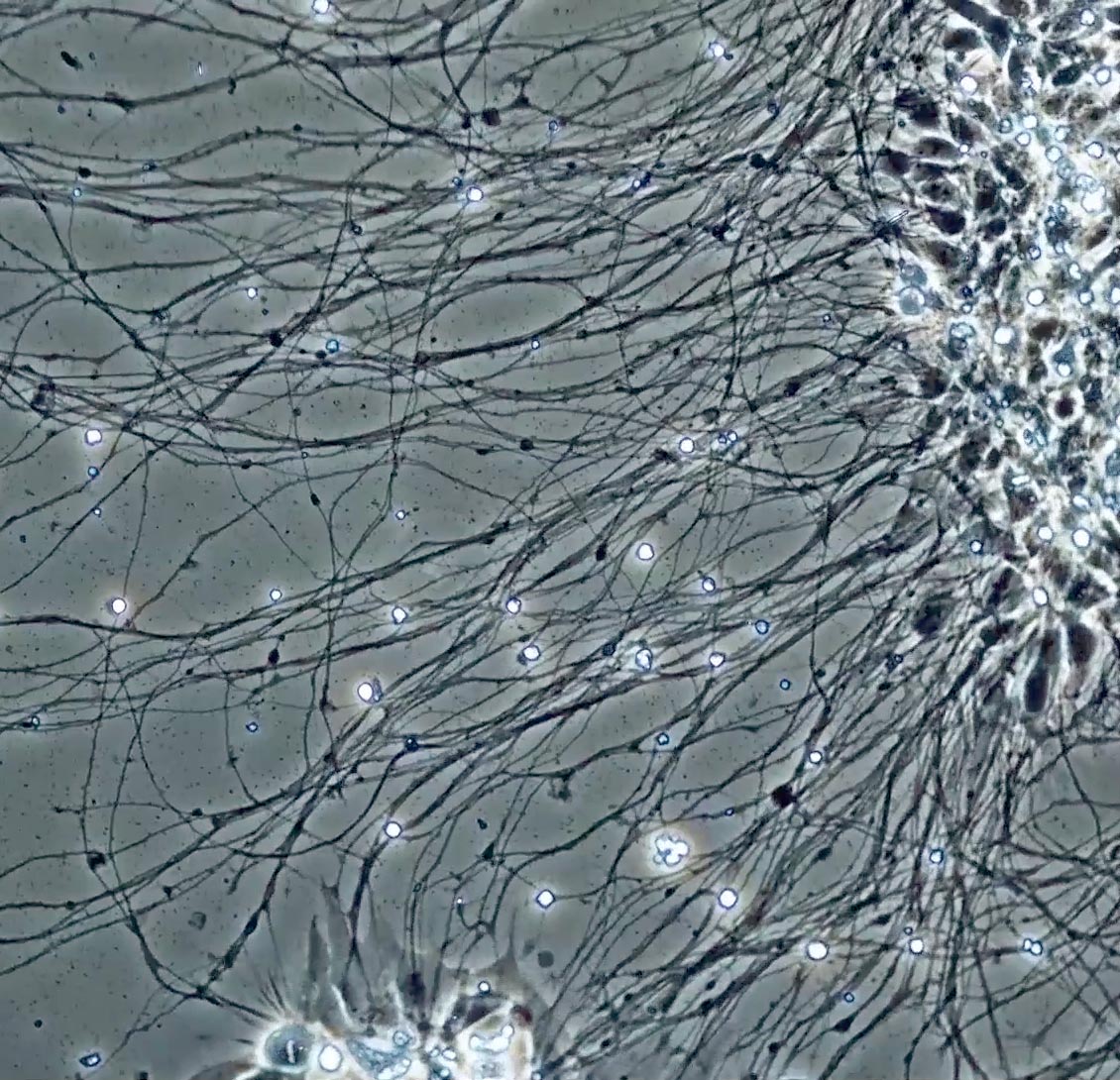

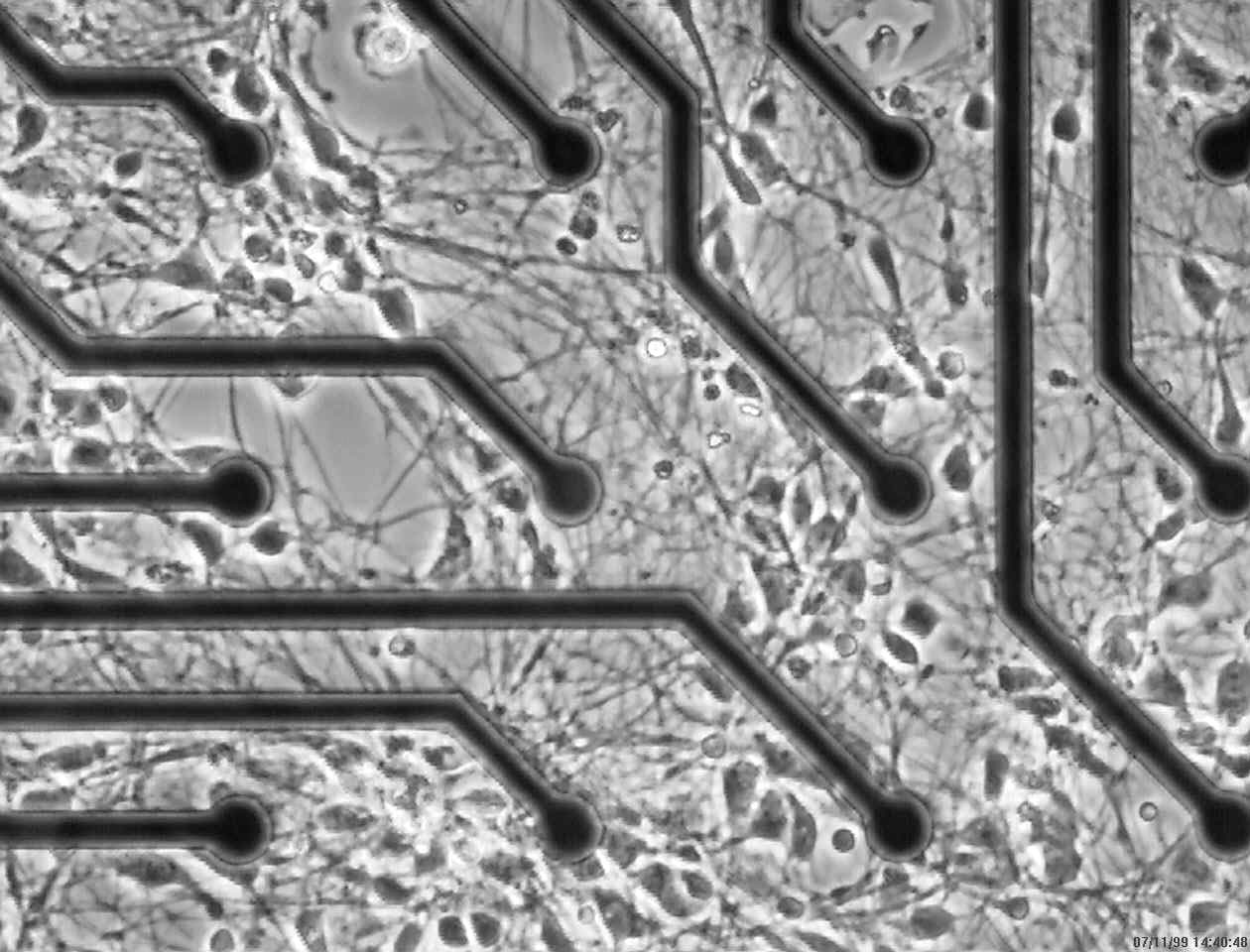

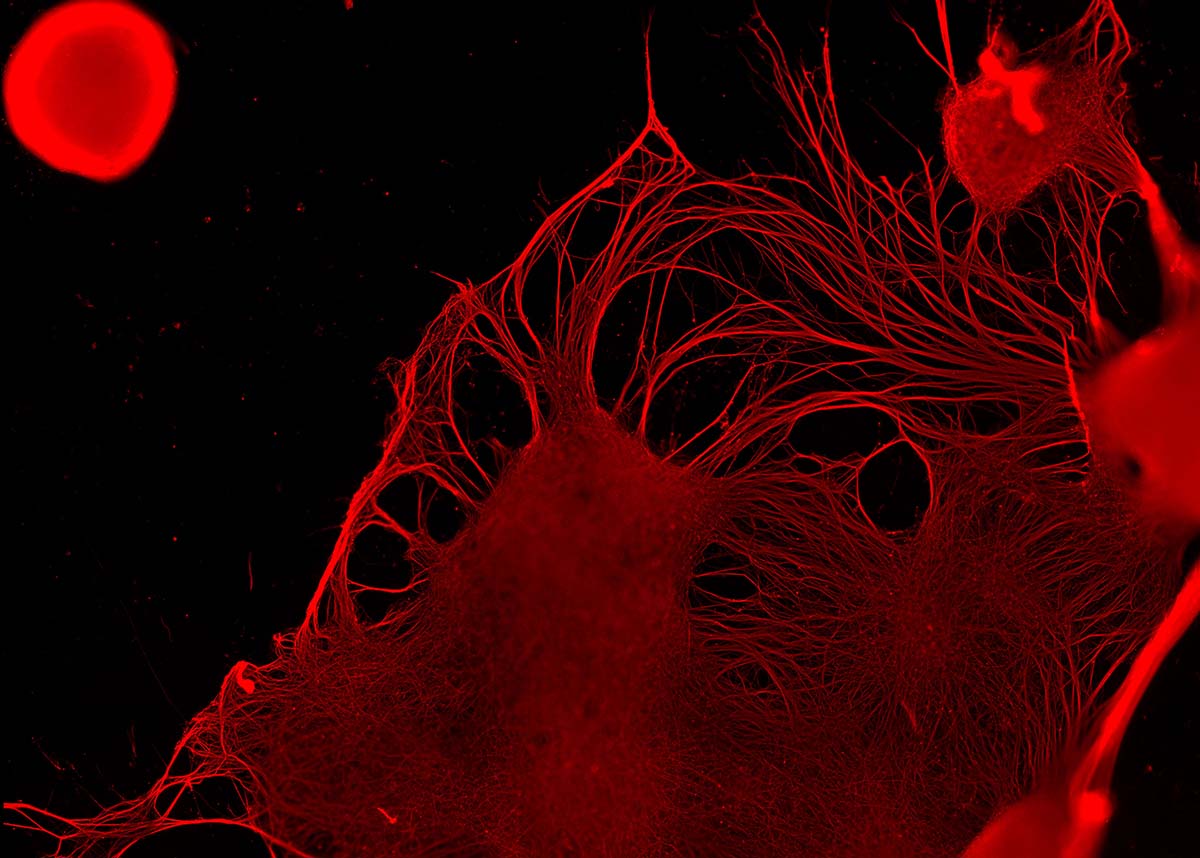

In 2001 we developed a project titled MEART – our first project that used neural networks (more about the project – http://guybenary.com/work/meart/). Neurons are cells that cant be frozen and they do not proliferate. Therefore, for MEART we needed to use Primary neural tissue (we couldn’t purchase neurons as cell lines), Furthermore, we did not have access to an electrophysiology system so we formed a collaboration with Dr Steve Potter, a neuro-scientist from Georgia Tech in Atlanta USA, and worked together in the development of MEART. The cells (neurons) we used for MEART were the same cells (neurons) he used for his own research originated from a rat (primary cells) and their use was cleared by Potter’s ethic approvals. Potter’s lab had dishes of neural networks that they used for their experiments and MEART used the same neural networks for its performances. We used the internet to connect between the neural networks in Atlanta to MEART that performed in various locations around the world. An interesting fact was that when MEART performed we always had 2 experiments on the go: 1. a cultural one happening within the gallery space and 2. A scientific one – where researchers from Potter’s lab we looking at how the neural networks respond to the stimulations that they received via MEART’s robotic body.

In 2007 we developed another project with Dr Steve Potter – Silent Barrage. We used the same idea of using the labs in-vitro neural networks of mouse primary neurons.

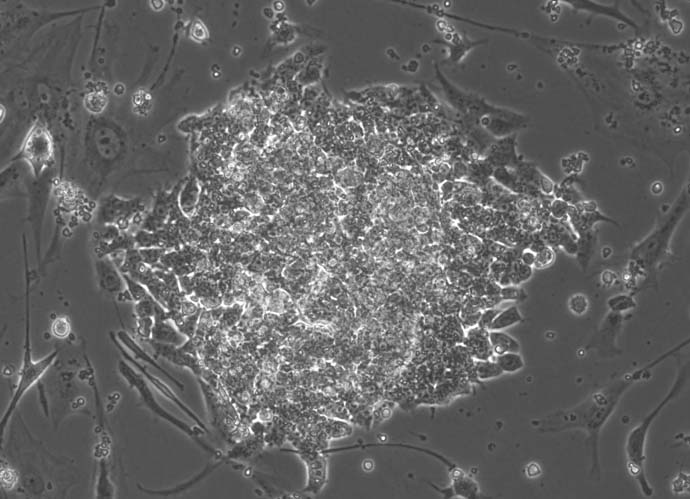

In 2008 the media became saturated with news of the development of a new stem cell technology known as Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSc). The iPSc technology was pioneered by Professor Shinya Yamanaka who showed that the introduction of four specific genes could convert adult cells into pluripotent stem cells. Yamanaka was awarded the 2012 Nobel Prize, along with Sir John Gurdon, for the discovery that mature cells can be reprogrammed to become stem cells. In layman’s terms, the iPSc method transforms adult specialised cells into a form that is equivalent to stem cells, which are capable of becoming any other type of cell in the body (skin, liver, muscle, neuron, etc.). The process involves re-programming their ‘software’ (genome), and coaxing them back into their embryonic state. The discovery of this biological alchemy intrigued us. Questions regarding how we are able to deconstruct, manipulate and re-assemble the microscopic building blocks of life in completely new ways, as well as the increasing ethical dilemmas and discourses associated with iPSc, gave us a new insight into how malleable and fragile our bodies really are.

Around this time, I had a conversation with a good friend of mine, a Bulgarian artist Boryana Rossa who criticised artists using the biological material of other species. She questioned the ethical aspect of this practice and asked why human material was not being used. I had to concede that MEART and Silent Barrage both relied on mouse and rat neurons grown over the MEA interface, a standard scientific practice, as human brain cells were (up until this point) out of the question, as there was no way to harvest brain cells without causing fatal harm. However, the discovery of iPSc technology appeared to offer a way to safely use human cellular material.

In potentia (2013) was the first project we used iPSc technology. We were looking at ways to assess its possibilities and try to problematize it so we could explore the ethical, philosophical and social implications of this revolutionary technology. We deliberately selected human foreskin cells as a starting point with the aim of reprogramming them into stem cells, and then into brain cells. We purchased the human foreskin cells from a commercial company (Thermo fisher, Catalog number: C0045C). We aimed to highlight the absurdity of the scenario; to reverse-engineer foreskin cells, and from this material, create a living ‘brain’, and so the project was affectionately given the working title of ‘Project Dickhead’. By positing an absurd scenario (transforming foreskin cells into neurons), in potēntia not only challenges the belief that iPS helps resolve the ethical dilemmas surrounding human embryonic stem cell research, but also raises ethical concerns regarding the relative ease with which human cell samples can be obtained (such as the purchasing of foreskin cells from an online catalogue).

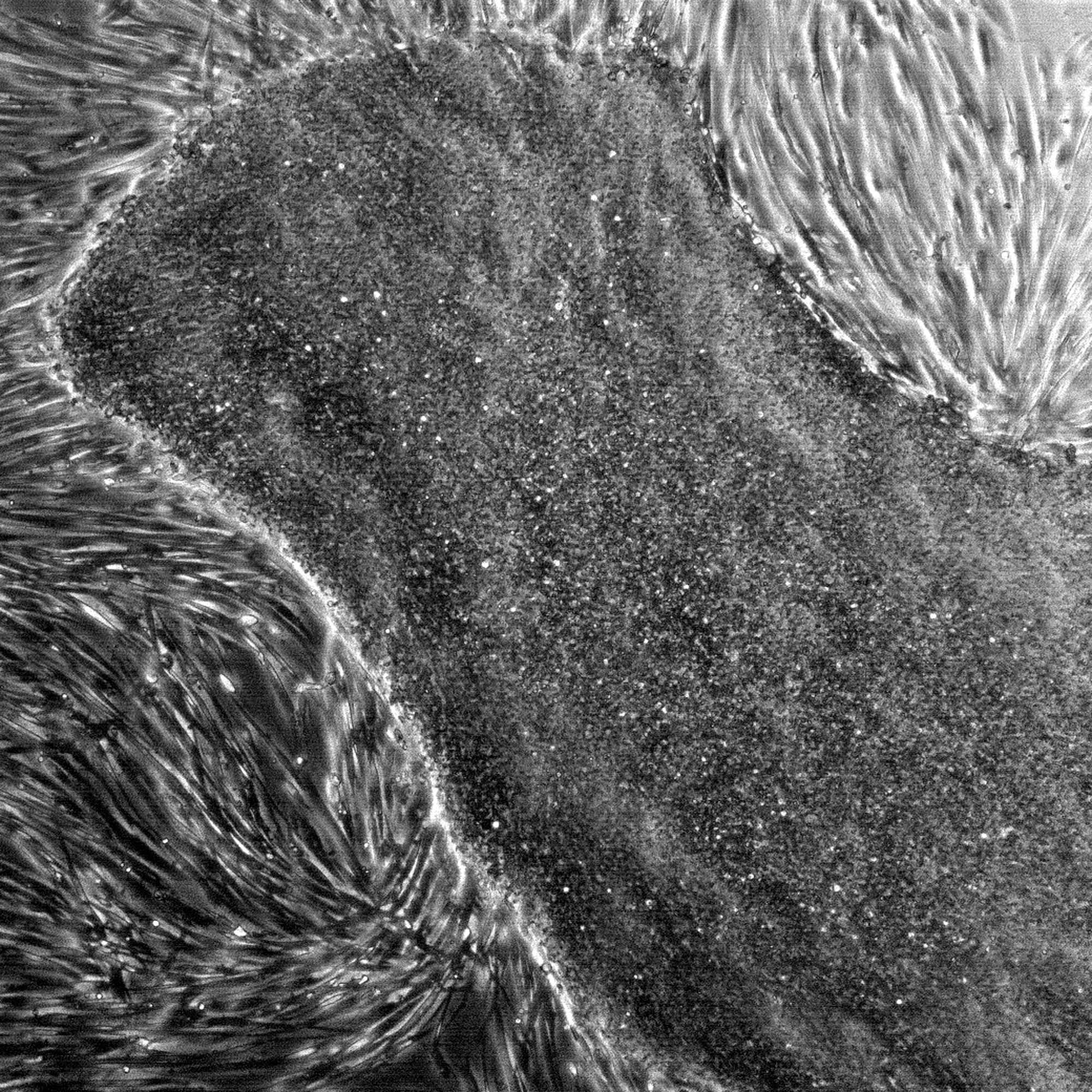

In 2015 we developed the project titled cellF. You can read more about it in one of our previous blog posts. cellF was funded by a Creative Australia Fellowship from Australia Council for the Arts to create a cybernetic self-portrait of mine (Guy Aen-Ary). I had a biopsy taken from my arm, and cultivated my skin cells in the labs of SymbioticA at UWA, then froze them cryogenically and shipped them to Barcelona, where I collaborated with Dr Michael Edel to reprogrammed the cells to stem cells. Then I shipped them back to Perth where we differentiated them to neural networks and grew them over MEA dishes to create my “external brain” or my surrogate performer known as cellF.

We continued to explore the artistic potential of the iPS technology in our recent project Bricolage. In Bricolage we created autonomous, animated, living, biological entities that have the ability to self-assemble. The automatons are made from bio-engineered human heart muscle cells that grow on bodies (scaffolds) made of silk. The muscle cells beat in real time, manipulating the automatons’ movement, and at times self-assemble to create a larger structure visible to the naked eye of gallery attendees.

Similar to neurons, heart muscle cells (cardio-myocytes) cannot be harvested without compromising the donors health. The stem cells that we are using to transform into beating heart muscle cells have originated from a drop of blood from consented anonymous donors. We reprogrammed blood cells from human donors to become stem cells using iPS technology and then used differentiation protocols to transform these cells to cardio myocytes or heart muscle cells. Exploring this alchemical process of the conversion of a drop of blood into a living animated entity – Technology that needs to be explored from a cultural perspective. A challenging and disturbing prospect.

We are currently in the initial stages of developing a new project titled ‘Revivification’. The intention is to create an in-vitro driven surrogate performer for one of the world’s most prolific experimental composers – Alvin Lucier. We have successfully gotten the cell donation from him (with his full consent of course) and now plan to grow organoids that will interface with the outside world via a robotic body. We are in discussions with him at the moment to determine the sort of embodiment we will create for his “external brain”.

By re-programming human cells, either purchased from on line catalogues or from human donors, iPSc technology helps us to create custom palettes of various materials. By hacking into the source cell’s software and manipulating the genetic make-up of the cells, we can craft the building blocks necessary for the creative process of producing our future work.